Setting

Scholars call Isaiah 1-39 “First Isaiah.” There is general agreement that the oracles in these chapters originally derive from Isaiah Ben Amoz and/or people associated with him. Some scholars argue that the underlying materials in First Isaiah were heavily edited in later centuries.

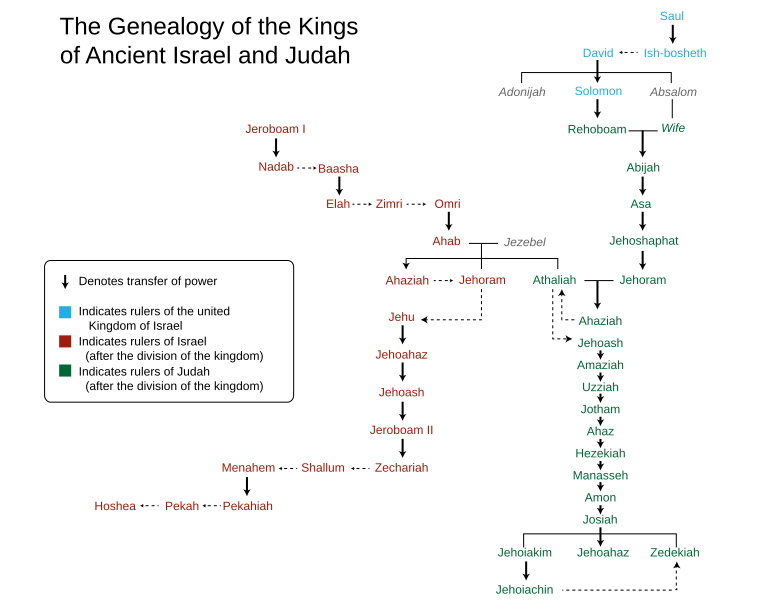

Verse 1 tells us that the text presents “the vision” (chazon) of Isaiah concerning Judah and Jerusalem during the time of Kings Uzziah, Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah. By this time the Jewish nation had been divided into the Northern Kingdom of Israel and the Southern Kingdom of Judah. The Kingdom of Judah encompassed the holy city of Jerusalem, which contained the First Temple originally built by King Solomon. This graphic shows the Kings of Israel and Judah:

It’s difficult to know precisely when some of these different Kings ruled. There is extra-Biblical (archeological and textual) evidence, however, to support the existence of many of these Kings, and we do know the dates of some key events mentioned in the narratives. During the period encompassed by this part of Isaiah, Israel and Judah came under increasing pressure from the Kingdom of Assyria.

The Biblical text tells us Uzziah reigned for 52 years. Judah became powerful and prosperous under Uzziah, but the Bible depicts him as deeply flawed. Uzziah’s son, Jotham, took the throne when Uzziah was struck with leprosy for offering incense in the Temple — an act seen as an usurpation of Uzziah’s authority. Only the Priests, who had been consecrated to God, were supposed to perform this function. Jotham, the Bible says, reigned for 16 years until he was deposed by a group that supported his son, Ahaz. Jotham is generally depicted as a good King in the Bible, but not a perfect one, particularly because Jotham failed to preserve the overall morality and piety of the people. Ahaz is depicted in the Bible as an evil King who gave in to the Assyrians, both politically and religiously. Upon his death after 16 years in power, Ahaz was succeeded by his son Hezekiah, who reigned for 29 years according to the Bible. Hezekiah, the Bible says, was a highly righteous King, who rolled back the syncretism introduced by Ahaz — although, again, not a perfect one.

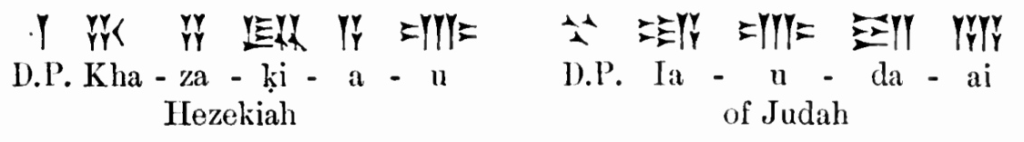

During Hezekiah’s reign, the Northern Kingdom of Israel was destroyed by King Sargon of Assyria. After Sargon died his son, Sennacherib, became King of Assyria and attacked Judah. Sennacherib’s army laid siege to Jerusalem, but, according to the Bible, God miraculously destroyed the Assyrian army and the siege was turned away. There is an Assyrian inscription which admits that Hezekiah did not submit to Sennacherib but which claims Hezekiah later paid him tribute money.

Here’s a picture of the “Sennacharib Prism,” which contains the Assyrian inscription:

Here’s a translation of the cuneiform on the Sennacherib Prism that mentions Hezekiah:

Here’s a portion of the wall built by Hezekiah to withstand the Assyrian siege:

And here is part of the Siloam Tunnel, dug by Hezekiah to provide water to Jerusalem during the siege:

The oracles in First Isaiah, then, cover a huge amount of territory — a period of about 64 years, from the end of Uzziah’s reign until the start of Hezekiah’s — during a tumultuous time in the life of Israel and Judah. It’s important to remember that the oracles in First Isaiah relate to specific events or issues in Judean society during this stretch of time. We are not entirely sure how these oracles were recorded and collected for publication, either in their original form or in the final canonical form of the book of Isaiah. We might imagine Isaiah sitting at his desk feverishly writing on a scroll with a quill pen, but that is not the likely scenario. It’s more likely that there were scribes attached to Isaiah and his school or movement, who perhaps published some of Isaiah’s sayings at critical times and then arranged and edited them into collections.

As we mentioned in our Introduction and Overview, Prophets played a unique role in ancient Israel during the time of the Kings. There was no concept of “separation of religion and state” in ancient Israel or otherwise in the ancient near east. However, in ancient Israel and Judah, the King and the Priests played different official functions under the Law. Prophets, in contrast, did not have an official civic function under the Law. Nevertheless, important Prophets, including Isaiah, could influence civic and religious policy. At the same time, Prophets, again including Isaiah, could criticize both Kings and Priests for failures to fulfill their roles, in particular in leading the nation to follow God’s Law and enact justice. Prophets were consulted for insight from Yahweh about momentous decisions, but their role usually was more about forthtelling — explaining why things are the way they are — than foretelling the future.

General Themes

Chapters 1-6 of First Isaiah establish what will become a familiar pattern of alternating oracles of judgment and oracles of hope. Notice that the oracles of judgment focus on the decline of the nation and of its cities — its cultural, economic, and religious centers, including in particular Jerusalem. As 1:7 puts it, “Your country lies desolate, your cities are burned with fire. . . .” The judgment oracles often sound xenophobic to our modern ears: 1:7 further says that, “in your very presence aliens devour your land; it is desolate, as overthrown by foreigners.” One of the central themes of the Law was that Israel should remain distinct from foreign idolatrous nations.

Focus Sections

Our first “focus” section, 1:18-26, includes a famous text: “Come now, let us reason [argue it out] together.” Notice God’s appeal to the people to enter into discussion or argumentation with God. God judges the nation’s unfaithfulness, but continually remains available for renewal if the nation wishes to return to Him. This section also establishes God’s primary complaints against His people: “Everyone loves a bribe and runs after gifts. They do not defend the orphan, and the widow’s case does not come before them.”

Some questions on this section:

- Do you ever hear God’s invitation to reason / argue things out?

- What do the images of scarlet / crimson sins and snow / white wool suggest for you?

Our second “focus” section, 2:1-4, illustrates the kind of eschatological hope continually held out in Isaiah in between the oracles of judgment. It also contains a famous line about “beating swords into plowshares.” Because it is an eschatological vision, we should be careful about interpreting these images too literally. A tradition did develop among some Jewish interpreters, however, that imagined a literal future highway running from surrounding nations into Jerusalem and to God’s Temple. Notice that there is an apparent contrast here from the seeming xenophobia of the previous oracles of judgment: the nations are welcomed into Jerusalem. This vision reverberates into the New Testament — compare Revelation 21:24-27, in which the nations are welcomed into the New Jerusalem.

Some questions on this section:

- How do you understand the hope offered in this section? Can a hope like this still sustain us today?

Our third focus section, 3:16 to 4:1, is part of a judgment oracle. It can sound sexist to modern ears. The theme, however, is about how the elites of Judean society had adopted Assyrian fashions, aspirations, and manners. They had become arrogant and secure in their wealth, disregarding the threat Assyria posed to the basic identity and existence of God’s people. Notice that God appears as a prosecutor arguing his case as well as the Judge (3:13-14).

Some questions on this section:

- How would you compare God’s invitation to argument in 1:18 with his argument in this oracle?

- What do you see as the core evils identified in this oracle? What might be an analogous warning for us today?

Our final focus section, 6:1-13, presents an awesome vision of Isaiah before the Heavenly Throne. Compare this vision with John the Seer’s vision in Revelation 4. This section also includes the famous scene in which a seraph purifies Isaiah for prophetic speech with a hot coal.

- What does Isaiah’s vision tell us about God? What might it say about our practices of prayer and worship?

- Have you ever experienced God’s purification as a preparation for some ministry or other part of your life?