Background

Chapters 1-12 concerned Yahweh’s judgments and promises regarding Judah and Jerusalem. Chapters 13-23 expanded the theme of judgment and promise to the nations. Chapters 24-27 widen the circle so that Yahweh’s judgment and promise become cosmic and scope. As Brueggemann notes, in chapters 24-27, “Israel’s traditional, long-established understandings of its life and the way Yahweh works in its life have been pushed to the cosmic, because the truth of God’s gospel can no longer be resolved or enacted in what is available of human history.” (Brueggemmann, Isaiah 1-39, 188.) Many scholars argue that chapters 24-27 contain material that dates after the surrounding oracles in First Isaiah, perhaps even as late as the Ptolemaic or Seleucid periods, after the Second Temple was built but before the Hasmonean and Roman periods.

Chapters 28-31 seem to return to more immediate and local themes, particularly concerning the danger to Judah of an alliance with Egypt. Scholars generally agree that these chapters, like chapters 1-23, are closely connected with the Eighth Century Prophet Isaiah ben Amoz. Chapters 32-33, in contrast, return to broader apocalyptic themes.

Chapters 34-35 continue to expand the general themes of judgment and promise, again with cosmic dimension. The theme of chapter 35, Bruegemann suggests, is “homecoming.” As we’ll see next week, in canonical context, chapters 34 and 35 provide a bridge to the next section of Isaiah concerning the good king, Hezekiah.

Focus: 25:1-10

This section is part of the “cosmic” cycle of judgment and promise in First Isaiah. The cosmic vision of 25:6-8 is picked up in various places in the New Testament. Jesus’ miracle of turning water into wine at Cana (John 2:1-11), for example, picks up the theme of eschatological abundance in Isaiah 25:6. Isaiah 25:7-8 is echoed in the last judgment scenes of Revelation 20:11 to 21:4:

Then I saw a great white throne and him who was seated on it. The earth and the heavens fled from his presence, and there was no place for them. And I saw the dead, great and small, standing before the throne, and books were opened. Another book was opened, which is the book of life. The dead were judged according to what they had done as recorded in the books. The sea gave up the dead that were in it, and death and Hades gave up the dead that were in them, and each person was judged according to what they had done. Then death and Hades were thrown into the lake of fire. The lake of fire is the second death. Anyone whose name was not found written in the book of life was thrown into the lake of fire.

Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and there was no longer any sea. I saw the Holy City, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride beautifully dressed for her husband. And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, “Look! God’s dwelling place is now among the people, and he will dwell with them. They will be his people, and God himself will be with them and be their God. ‘He will wipe every tear from their eyes. There will be no more death’ or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away.”

Discussion Questions:

- How can we hold together — in the Isaiah text and in the Christian appropriation of the theme — the cosmic word of judgment and the cosmic word of restoration?

- Does the inter-textual flow of Isaiah 1-35: local → worldwide → cosmic suggest anything to you? How do you see and experience God’s words of judgment and promise as local, worldwide, and cosmic?

Focus: 27:1-2, 12-13

The figure of “Leviathan” is drawn from ancient near eastern mythology. It appears in Job 3 and is depicted in depth in Job 41. It also is mentioned in Psalm 74 and 104 as well as here in Isaiah. Leviathan was an uncontrollable creature, an agent of chaos. The “formless and void” earth surrounded by the waters in Genesis 1:2 and the “serpent” in the Garden of Eden in Genesis 3 invoke the same mythic concepts. The imagery of Revelation 12 similarly includes a “dragon” or “serpent” that is identified with Satan.

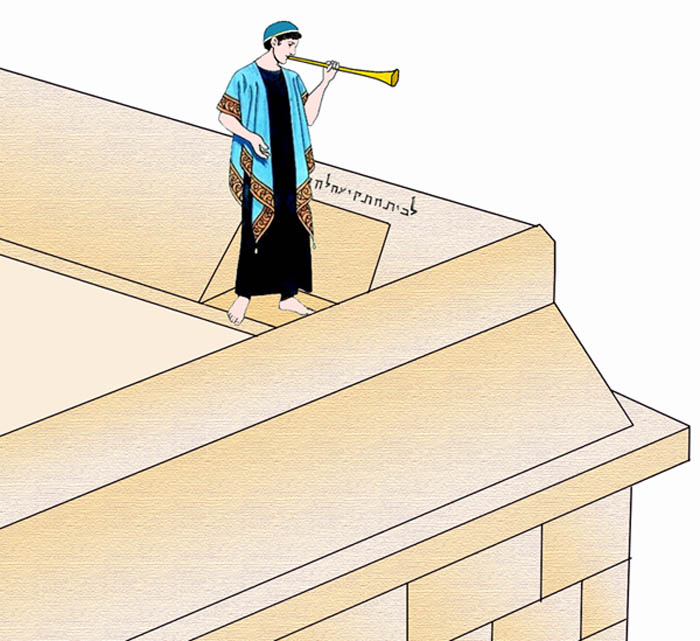

Verses 12-13 depict the gathering of the Jewish diaspora to Jerusalem. The beginning of this return is signaled by a trumpet blast. The featured image at the top of this post is the “Trumpeting Place Stone” unearthed on the Temple Mount in 1968 by archeologist Eliot Mazar. Archeologists believe the stone was a marker on the southwest corner of the Second Temple that identified the place for a Priest to blow a trumpet that signaled the beginning of the Sabbath, as depicted below. The trumpet blast, then, would have carried various religious meanings for an ancient Jew, including the start of the Sabbath rest.

Again, in the New Testament, there is an echo of this signal in the seven trumpets of Revelation, as well as the trumpets in 1 Corinthians 15 (“Listen, I tell you a mystery: We will not all sleep, but we will all be changed— in a flash, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet. For the trumpet will sound, the dead will be raised imperishable, and we will be changed”); 1 Thessalonians 4 (“For the Lord himself will come down from heaven, with a loud command, with the voice of the archangel and with the trumpet call of God, and the dead in Christ will rise first”); and Matthew 24 (“And he will send his angels with a loud trumpet call, and they will gather his elect from the four winds, from one end of the heavens to the other”). The New Testament, then, seems to add the theme of resurrection to the Isaianic theme of return.

Discussion Questions

- When, and how, have you experienced “Leviathan?” How do you understand “Leviathan” in relation to God?

- Why do you think the image of a trumpet blast is used so often in the Bible? If you have tried to wrestle with “Leviathan,” have you ever heard the trumpet blast? Do you look for a trumpet blast yet to come?

Focus: 28:7-17 and 35:3-10

The focus section in chapter 28 skewers the hypocrisy of the existing political and religious leaders in Jerusalem, who place unnecessary burdens on the people. Verses 7-8 refer to a Canaanite ritual for the dead that involved all night feasting and drinking. God’s response refers to a ritual for consecrating a new public building — the dedication of a cornerstone, a common practice even today. The building is constructed on the lines of justice (mishpat) and righteousness (tsedeqah) — broad terms for a peaceable and good community.

Jesus regularly tussled with the Pharisees, a Second Temple-era group that emphasized ritual purity and fidelity to the Torah, for what he saw as their oppressive and hypocritical legalism. For example:

What sorrow awaits you teachers of religious law and you Pharisees. Hypocrites! For you are careful to tithe even the tiniest income from your herb gardens, but you ignore the more important aspects of the law—justice, mercy, and faith. You should tithe, yes, but do not neglect the more important things.

Matthew 23:23 (NLT)

The Apostle Paul picks up on these theme and identifies this new building as the ekklesia, in which Gentiles have also been included:

Consequently, you are no longer foreigners and strangers, but fellow citizens with God’s people and also members of his household, built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets, with Christ Jesus himself as the chief cornerstone. In him the whole building is joined together and rises to become a holy temple in the Lord. And in him you too are being built together to become a dwelling in which God lives by his Spirit.

Ephesians 2:19-21 (NIV)

The focus section in Chapter 35 continues the theme of restoration. The Gospels identify the miracles of Jesus as signs that the Kingdom of God has arrived as described in verses 5 and 6. The themes of streams of water bursting out of the desert, the “highway” traveled by God’s people back to Jerusalem, and the processional return with joy and singing, appear many times in the Hebrew Scriptures. For example, Miriam and Moses led triumphant songs after the Israelites escaped from Egypt by processing through the parted waters (Exodus 15); David danced at the head of a procession when the Ark of the Covenant was retrieved from the Philistines (2 Samuel 5:17 to 6:4); the prophet Ezekiel pictures a river flowing out into the land from the Temple (Ezekiel 47). We have already seen, this vision of the “highway” from all points of the world back to Jerusalem is a consistent eschatological theme in Isaiah.

Discussion Questions

- In our time and place, do you observe patterns that you could describe as “rituals” of oppression, excess, and death? How might the rituals or practices of God’s people establish community built on a different foundation?

- Notice how Paul, in the passage from Ephesians quoted above, converts the physical reality of the Temple into the spiritual / communal reality of the ekklesia. What do you think of this use of Isaiah’s Temple theology? Is the ekklesia, the Church, the fulfilment of Isaiah’s vision?/1/

Notes

/1/ Many scholars believe Ephesians is pseudepigraphic — that is, that it was not written by Paul even though it is attributed to Paul. This was not necessarily a nefarious practice in the ancient world, although the presence of pseudepigraphic materials in the New Testament does raise interesting questions about canon and interpretation. One reason among many for the possible pseudepigraphic status of Ephesians is a seemingly much stronger emphasis on the ekklesia than appears in the undisputed Pauline corpus. For a good discussion on the provenance of Ephesians — with a conclusion that it is, in fact, an authentic correspondence of Paul addressed to the Christian community in Laodicea — see Douglas Campbell, Framing Paul: An Epistolary Biography (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans 2014), 309-38.