Introduction

The last three chapters of “First Isaiah” shift abruptly from poetic oracles to narrative. The narrative occurs during the reign of King Hezekiah. Recall that Hezekiah is the last of four Kings of Judah mentioned in connection with the “vision” of Isaiah ben Amoz in Isaiah 1:1, and that Hezekiah, on the whole, is regarded as a good King in the Bible. Chapters 36 and 37 depict Hezekiah resisting the siege of Jerusalem by the armies of King Sennacherib of Assyria. Chapter 39, however, depicts a devastating mistake, stemming from a moral failure, by Hezekiah in relation to Babylon.

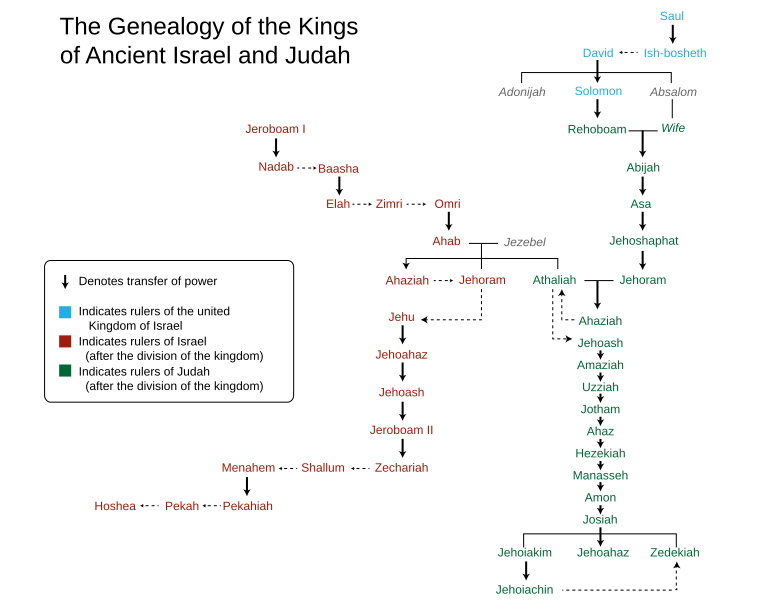

Here again is the chart of the Kings of Israel and Judah:

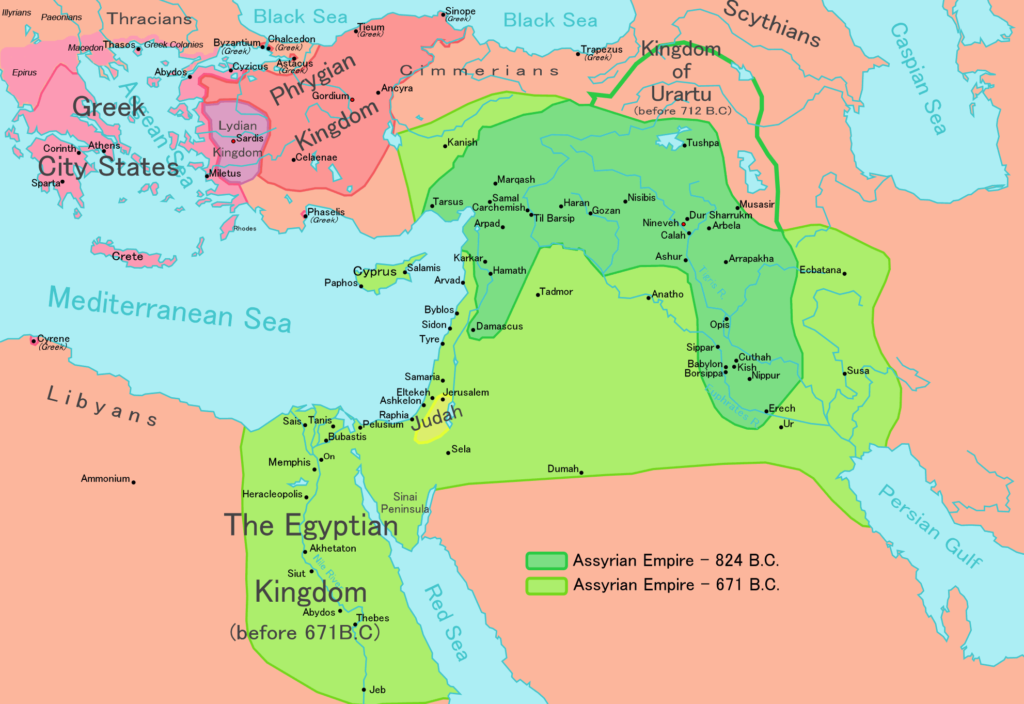

Remember that Egypt, Assyria, and Babylon were the great powers in the ancient near east in the time leading up to and encompassing Isaiah. Assyria was on the rise. At its height, running from one of Sennacherib’s predecessors, Tiglath-Pileser III through his immediate successor, Esarhaddon, the Neo-Assyrian Empire dominated Babylon, Egypt, and the Levant:

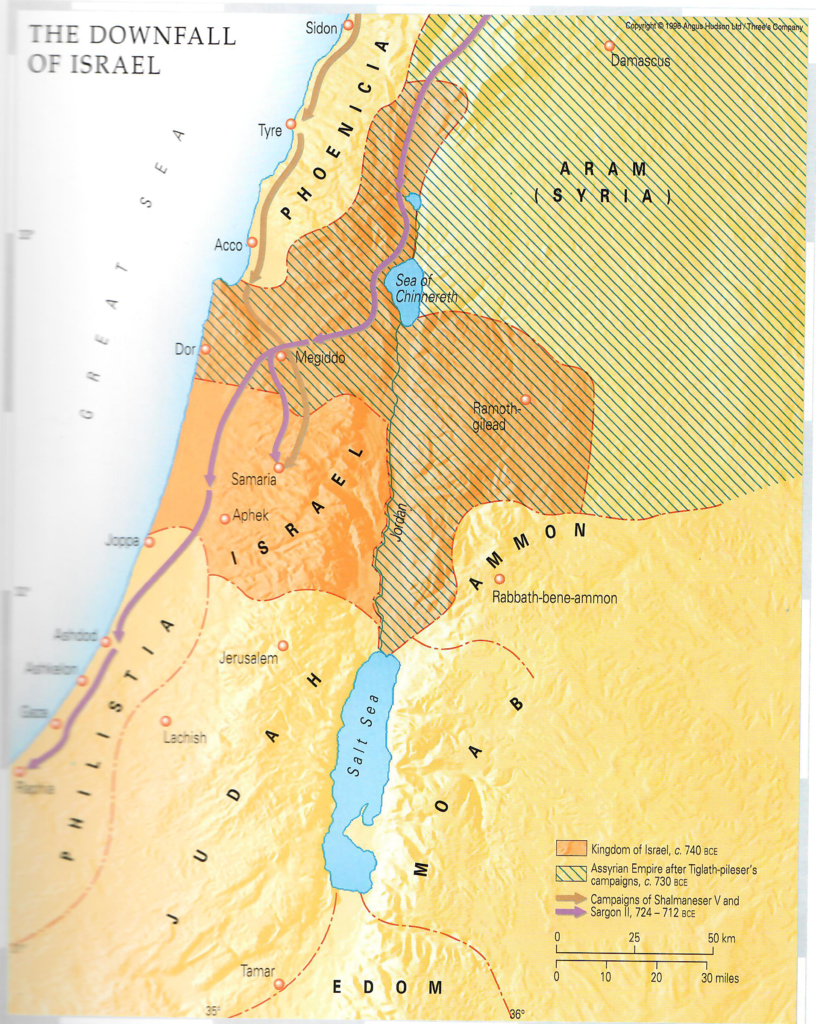

Tiglath-Pileser III had executed a campaign that turned Israel into a vassal state, with a requirement to pay heavy tribute to Assyria:

King Hoshea of Israel tried to break with Assyria by forming an alliance with Egypt. Tiglath-Pileser’s successor, Shalmaneser V, then attacked Israel, and besieged and destroyed its capital, Samaria:

Sargon II, who claimed he was the son and rightful heir of Tiglath-Pileser III, usurped the Assyrian throne from Shalmaneser. Early in his reign Sargon contended with internal civil unrest while launching a costly campaign in against the Kingdom of Urartu in the north. He also successful attacked Babylon and was proclaimed “King of Babylon.” He was killed in battle, however, when he recklessly personally led a military charge in a campaign against a rebellious Assyrian province.

Sennacherib was Sargon’s son, and as crown prince, managed the administration of the empire while his father was away on campaigns. Available records suggest Sargon and Sennacherib had a good relationship. This relief shows Sargon on the left; the figure on the right may be Sennacherib:

Isaiah 37 and 37: Sennacherib’s Siege of Jerusalem

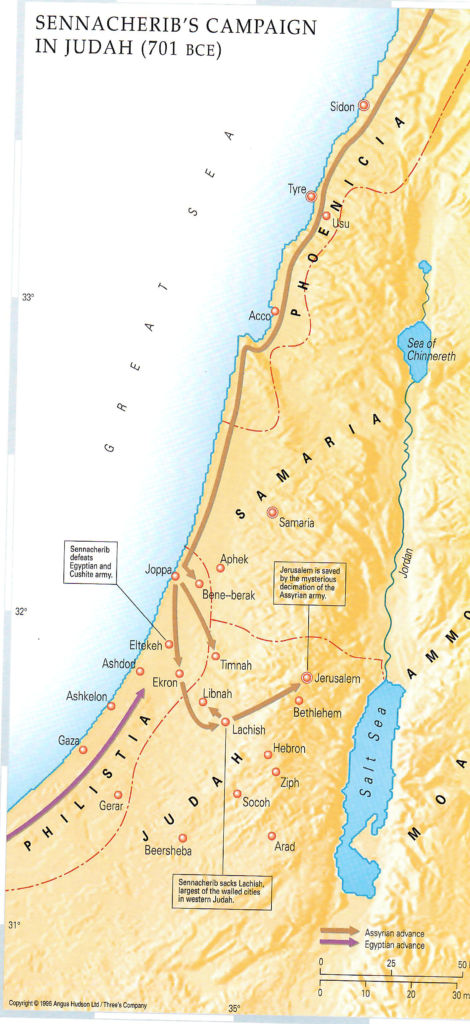

After Sargon’s death, Sennacherib assumed the Assyrian throne. He turned Assyria’s attention back to the Levant and mounted a campaign against Judah. That campaign is the subject of Isaiah 36 and 37:

The text mentions that “the Rabshakeh” — a term for a high official, a “Cup Bearer” or “Chief Steward” — to Jerusalem after capturing the major “fortified cities” of Judah, including Lachish. This relief depicts Sennacherib giving the order to destroy Lachish. The inscription reads: “Sennacherib, the mighty king, king of the country of Assyria, sitting on the throne of judgment, before (or at the entrance of) the city of Lachish (Lakhisha). I give permission for its slaughter”:

This panel shows an Assyrian siege engine, comprised of a ramp, an armored cart, and archers, mounting the walls as Lachish:

In our introduction to First Isaiah we included some more information about Hezekiah’s defenses during the siege of Jerusalem. Sennacherib’s records of the Jerusalem siege reads as follows: “As for Hezekiah … like a caged bird I shut up in Jerusalem his royal city. I barricaded him with outposts, and exit from the gate of his city I made taboo for him.” The historical context of Isaiah 36 and 37, then, is not in doubt. Israel had been devastated by Assyria under Tiglath-Pileser III and Shalmanesar V, and Judah was threatened by Sennacherib, culminating in a siege of Jerusalem while Hezekiah was King of Judah.

Sennacherib’s account of the Jerusalem siege, notably, does not state that he took the city. It is clear from the historical and archeological record, in fact, that Sennacherib withdrew without taking Jerusalem. The ultimate fall of Jerusalem occurred more than a century later, in 587 BC, when the city and the Temple were destroyed by King Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon.

The Greek historian Heroditus, writing several centuries after the events, said the siege was lifted because a plague of field mice destroyed the Assyrian’s equipment. The narrative in Isaiah 37:36, which also appears in 2 Kings 19, states that the “Angel of the Lord” killed 185,000 Assyrian soldiers overnight. Many historians and Bible scholars suggest that large numbers like this in ancient near eastern battle accounts — whether in the Bible or in Assyrian, Egyptian, or Babylonian accounts — are usually exaggerated. This might represent a sort of literary convention of the ancient near eastern battle account. Some historians and Bible scholars suggest that an outbreak of disease in the Assyrian camp — perhaps malaria or cholera — might have ended the siege.

Curiously, the narrative in Isaiah is the same as the parallel narrative in 2 Kings 18-19, except for one important detail. 2 Kings 18:13-16 states that, when the siege first began, Hezekiah paid a tribute of “all the silver that was found in the house of the Lord and the treasuries of the king’s house” as well as “the gold from the doors [and doorposts] of the temple of the Lord” — an act that the prophet surely would have viewed as cowardly.

Discussion Questions

- The Rabshakeh tries to spread fear among the Judean troops by speaking in the common tongue of Hebrew instead of the courtly language of the time, Aramaic. How do we respond to efforts to spread mass fear and panic?

- Hezekiah consults Isaiah, who counsels him to remain steadfast. In a time of crisis, do you consult “the prophets?” How? (Note: the Hebrew Scriptures are referred to as “the law, the writings, and the prophets.”)

- Hezekiah receives a letter from Sennacherib that frightens him. He goes into the Temple, spreads the letter before the Lord, and prays. Have you had an experience of “spreading” a troubling circumstance before the Lord? How did the Lord respond?

Isaiah 38 and 39: Hezekiah’s Weakness

Isaiah 38 and 39 turn to other events in Hezekiah’s life . There are parallel accounts in 2 Kings 20. In the account of Hezekiah’s illness we see a famous sign that has long puzzled interpreters: the shadow of a sundial goes backwards. (Is. 38:7-8.) A similar kind of event occurs in Joshua 10:12-13, where the Sun is observed to “stand still.” If these events were caused by the actual movements of the Sun or the Earth, the laws of gravity would have been suspended, which would end the universe as we know it. Of course, we could say that God is free to suspend the physical laws or their effects while keeping the universe intact, and perhaps that was the case. There are all sorts of claims that NASA or some other scientific group has confirmed a “missing day” in the records of space-time. These kinds of claims of “scientific” confirmation are mostly nonsense. Others suggest that these events correlate with solar eclipses, which seems more plausible. The most likely explanation is that these signs, to the extent they were actually experienced as the Biblical narratives suggest, were some kind of optical illusion.

In Isaiah 39 we more clearly see some of Hezekiah’s flaws. This is particularly the case in Isaiah 39. Trying to impress an envoy from Babylon, he shows off the royal treasury. When he hears from Isaiah that this act sealed Jerusalem’s future doom, he is glad that the last day will not occur in his lifetime.

Discussion Questions

- Have you ever experienced recovery like Hezekiah? How did you see God’s hand in it?

- What moral lessons might you gather from Isaiah 39? Is it right to discern “moral lessons” from this kind of Biblical narrative?