Introduction

In these chapters we move from “First Isaiah” to “Second Isaiah.” Recall that many scholars think “First Isaiah,” or at least substantial parts of it, dates to the prophet Isaiah ben Amoz, who lived before the Babylonian Exile, and that “Second Isaiah” (chapters 40-56) dates to the Persian and early Greek periods.

As always, it’s helpful to put this into a timeline:

| c.13th century | Exodus from Egypt: Moses leads Israelites from Egypt, followed by 40 years of wandering in the desert. Torah, including the Ten Commandments, received at Mount Sinai. |

| 13th-12th centuries | Israelites settle in the Land of Israel |

| c.1020 | Jewish monarchy established; Saul, first king. |

| c.1000 | Jerusalem made capital of David’s kingdom. |

| c.960 | First Temple, the national and spiritual center of the Jewish people, built in Jerusalem by King Solomon. |

| c. 930 | Divided kingdom: Judah and Israel |

| 722-720 | Israel crushed by Assyrians; 10 tribes exiled . . . . |

| 586 | Judah conquered by Babylonia; Jerusalem and First Temple destroyed; most Jews exiled. |

THE SECOND TEMPLE PERIOD | |

| 538-142 | Persian and Hellenistic periods |

| 538-515 | Many Jews return from Babylonia; Temple rebuilt. |

| 332 | Land conquered by Alexander the Great; Hellenistic rule. |

166-160 | Maccabean (Hasmonean) revolt against restrictions on practice of Judaism and desecration of the Temple |

| 142-129 | Jewish autonomy under Hasmoneans. |

| 129-63 | Jewish independence under Hasmonean monarchy. |

| 63 | Jerusalem captured by Roman general, Pompey. |

| 63 BCE-313 CE | Roman rule |

63-4 BCE | Herod, Roman vassal king, rules the Land of Israel; Temple in Jerusalem refurbished |

(CE – The Common Era) | |

| c. 20-33 | Ministry of Jesus of Nazareth |

| 66 | Jewish revolt against the Romans |

| 70 | Destruction of Jerusalem and Second Temple. |

In the timeline above, the nature and details of the early events through the reign of Solomon are debated by archeologists and other scholars. The archeological and extra-Biblical historical record becomes more clear around the time of the divided kingdom. As we discussed in connection with our study of “First Isaiah,” the Northern Kingdom of Israel was overrun by Assyria, while the Southern Kingdom of Judah, under King Hezekiah, survived a siege by the Assyrian King Sennacherib.

In the late 600’s BCE, the Babylonians were on the rise again in the ancient near eastern game of thrones. Assyria allied with Egypt against Babylon. Meanwhile, the Kings of Judah after Hezekiah, according to the Bible, were mostly a bad lot. Hezekiah’s successor, his 12-year-old son Menasseh, according to 2 Kings 21, “erected altars for Baal” and for “all the host of heaven” — minor deities other than Yahweh — in the Jerusalem Temple, and also “shed very much innocent blood.” In response, Yahweh promised that he would “wipe Jerusalem as one wipes a dish, wiping it and turning it upside down.” (2 Kings 21:13.) Manasseh’s son Amon followed in his father’s evil footsteps.

Amon’s son Josiah, according to 2 Kings 22, was a good King, who retrieved a neglected copy of the Torah from the Temple and sought to restore proper worship. God promised Josiah that his reign would be peaceful, but the oracle of judgment against Jerusalem remained.

Josiah was succeeded by his son, Jehoahaz, another bad king. Jehoahaz was locked up by the Egyptians, who installed his brother, Jehoiakim, as an Egyptian puppet. Jehoiakim paid heavy tribute to Egypt, and then became a vassal of King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon. When Jehoiakim tried to rebel against Babylon, he was destroyed by other local opportunistic tribes and succeeded by his son Jehoiachin. Nebuchadnezzar, apparently growing tired of the unrest, besieged Jerusalem, resulting in heavy tribute of treasure from the Temple and the palace, as well as the captivity of the Judean elite. (This period is the literary setting of the book of Daniel, who, with his three friends, is depicted among that elite captive class in Babylon.) (2 Kings 24-25.)

Nebuchadnezzar installed Jehoiachin’s uncle Mattaniah on the throne (or as a provincial governor) and renamed him Zedekiah. Zedekiah also tried to rebel, and Nebuchadnezzar again besieged Jerusalem. This time — in 586 BCE — the Temple was destroyed and the remainder of the population was taken into exile. (2 Kings 25.)

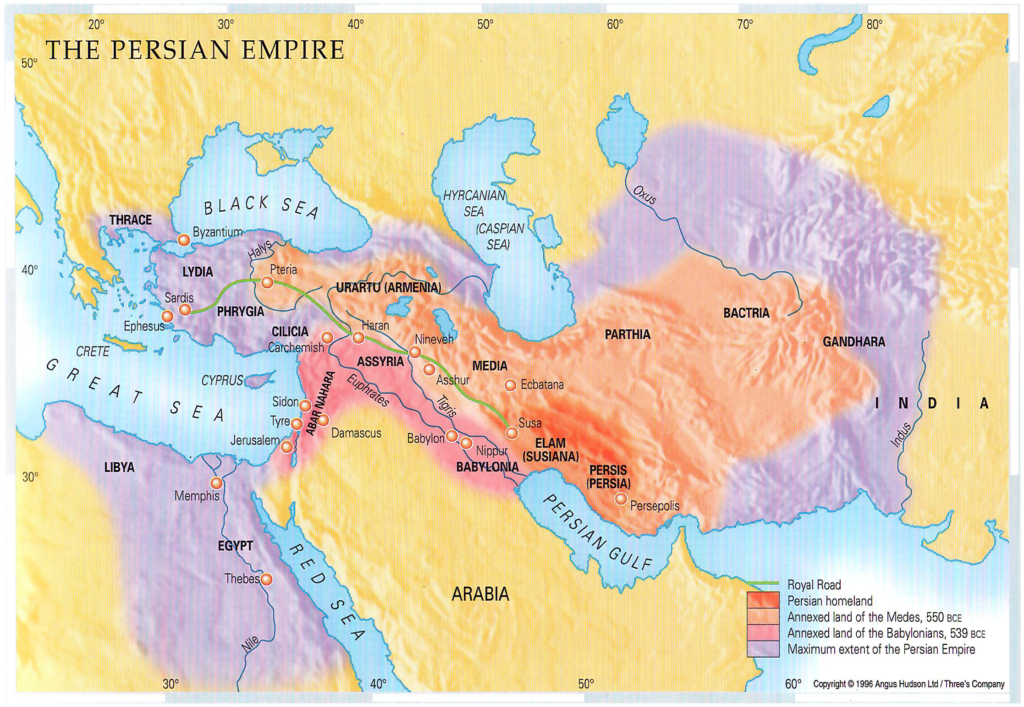

Meanwhile, a new empire was rising: the Persians. Starting under Cyrus the Great, the Persians conquered lands extending from Egypt into the Hindu Kush (modern-day India), including Babylon:

The Persian Empire subsequently engaged in an epic series of conflicts with the Greeks. On November 5, 333 BCE, an alliance of Greeks led by Alexander the Great won a decisive victory against Darius III of Persia, which inaugurated the Hellenistic Period.

At the start of the Persian Period, according to the Biblical text, King Cyrus the Great issued a decree allowing the Jewish exiles in Babylon to return to Jerusalem. The return, including the re-homing of the Temple vessels and the construction of the Second Temple, are described in the Biblical books of Ezra and Nehemiah. Ezra depicts Cyrus’ decree as a result of the “spirit of the Lord’s” influence on Cyrus. Archeological finds, including the famous “Cyrus Cylinder,” suggest that Cyrus adopted a general policy of allowing local cult centers to be reestablished. Cyrus is referred to obliquely “a victor from the east” (e.g., Isaiah 41:2) and directly (e.g., Isaiah 45:1) in Second Isaiah.

The texts we are studying this week, then, celebrate the return of the exiles under Cyrus. Remember that, when we studied the prophetic oracles in First Isaiah, we saw a pattern of judgment and promise: God would judge the nation’s sin by allowing it to be overrun by foreign powers, but He would also preserve a remnant that would take part in the eschatological renewal of the world. These chapters suggest the promised renewal has begun.

In the timeline above, notice that things do not go smoothly after the return. After Alexander the Great’s death, his empire fractured. The Hellenistic Seleucid authorities in Jerusalem tried to suppress Jewish religion. The Seleucid ruler Antiochus IV even placed a statue of Zeus in the Second Temple — likely referred to in the Bible as “the abomination that causes desolation.” (Daniel 11:31.) /1/ This led to the Maccabean revolt, followed by a period of independence under the Jewish Hasmonean Kingdom. Jewish literature about this period can be found in the “Apocrypha,” parts of which are considered canonical scripture by the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches, as well as in the works of Titus Flavius Josephus.

In 63 BCE, the Levant became subject to a new world power: Rome. A Roman Jewish vassal, Herod the Great, lavishly expanded the Second Temple, which some Jews welcomed but others saw as akin to the bad Kings’ deals with Assyria, Egypt, and Babylon. The New Testament Gospels are set in the period of Herod the Great and his sons, under Roman rule. This context shows why Jesus is depicted in Isaiah’s prophetic mold, offering words of judgment along with words of restoration for the Jewish people.

Focus: Chapter 40

Isaiah 40 is one of the most beautiful and resonant parts of the Hebrew Bible. Verses 1-4 are incorporated into a lovely section in Handel’s Messiah:

Verse 9 also is incorporated into the Messiah (I love when a countertenor sings it):

And verse 11 is part of another recitative:

The Gospel of Mark connects Isaiah 40:3 with John the Baptist. (Mark 1:1-4. In fact, Mark’s quote appears to combine Isaiah 40:3 with parts of Exodus 23:20 and Malachi 3:1.) Richard Hays notes that the Greek term in Mark 1:3, Kyrios (“Lord”) corresponds to the terms of divinity in Isaiah 40:3 (Elohim and Yahweh) suggesting that Mark’s Gospel identifies Jesus with God.

Verse 11 resonates in Christian piety with the theme of the “Good Shepherd” in the Gospels. The image of the shepherd, from the future King David, to texts such as Psalm 23, through the New Testament, is a vital Biblical theme.

Verses 12-26 echo another common theme in the Hebrew Scriptures: God is the ruler of creation. God’s rulership of creation is connected here with His sovereignty over human affairs and human nations.

Verses 27-31 remind Judah that God will not forsake His people. Parts of verses 28-31 appear on many Christian devotional items and in various popular praise songs.

Some questions on this chapter:

- In our present troubling times, as Advent approaches, can we still hear a voice preparing the way of the Lord? Can we still hear “good tidings?”

- How have you experienced God as a “shepherd?”

- What do verses 28-31 mean to you?

Focus: 42:1-9

Verses 1-4 present the first of four “servant songs” in Isaiah (the others are in 49:1-6; 50:4-11; and 52:13-53:12.) In the original horizon of Isaiah, the “servant” represents Israel. It is Israel’s mission to “bring forth justice to the nations” even though Israel will suffer in consequence of its calling.

Matthew’s Gospel says Jesus fulfilled this servant song (Matt. 12:1-21). Matthew uses this text to explain why Jesus was harassed by the Pharisees for feeding and healing people on the Sabbath.

Verses 5-9 of Isaiah 42 further amplify the servant’s missional role. The emphasis on giving sight to the blind and setting prisoners free also is a common theme picked up in the Gospels and elsewhere in the New Testament.

Some questions on this section:

- What does Matthew’s reworking of this servant song suggest to you? What does it tell us about Jesus? What does it tell us about our place in God’s missional community?

- Have you experienced or witnessed the kinds of things mentioned in verse 7 — whether literally or figuratively? What could it mean for us as a missional community to bring sight to the blind and to set prisoners free?

Focus: 43:25 to 44:5

This section first offers an apologetic for God’s judgment of Israel: from the time of Jacob through the time of the monarchy the people sinned. It then moves quickly to the present time of renewal in chapter 44. The renewal involves God’s “spirit” — ruach (breath) — which is likened to water pouring over dry ground.

The expectation that God’s “spirit” would accompany the eschatological renewal is common in the Hebrew Scriptures’ prophetic literature and is mirrored in the New Testament. Acts 2, for example, quotes a similar passage from Joel 2 to explain the Spirit’s presence at Pentecost.

- What do you think the pouring out of God’s “spirit” involves? Where do you see “dry ground” today?

Notes

/1/ The Biblical book of Daniel is set in the Persian period, but many scholars believe it was produced as a protest against the Seleucid oppression. Christian Millenarian movements, including present day “end times” preachers, typically interpret references to “the abomination that causes desolation” and other statements in Daniel, as they connect to related statements in the New Testament, as prophecies about future events relating to the second coming of Christ (called a “futurist” reading). The mainstream of Biblical scholarship, however, sees the New Testament’s references and allusions to Daniel as a protest against Roman rule and, at times, a backshadowing of the Roman destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE (called a “preterist” reading). In our immediate context, the “futurist” reading of these texts is part of why many conservative evangelical Christians view Donald Trump as the “new Cyrus.” Although Trump is not a prototypical “Christian leader,” they argue, God raised him up to allow the return of Christians from an exile imposed by the “radical left.” The claims of a massive conspiracy to “steal” the election is understood as part of the demonic plan, foreseen in scripture, to establish a new pagan world empire.