The Church in Rome

In the First Century CE — that is, within the decades after the death and resurrection of Christ — the church in Rome was one of the early Christian communities that developed in cities in the Roman world, in what is today Greece, Italy, Turkey, and the Middle East. You’ll recognize some of the names of these cities from Paul’s letters — Rome, Corinth, Thessalonica, Ephesus, Philippi. These churches reflect Paul’s missionary activity, described both in his letters and in the book of Acts. Others you’ll recognize from the text of the book of Revelation — including Ephesus as well, but also Smyrna, Pergamum, Thyatira, Sardis, Philadelphia, and Laodicia. These may represent another stream of Christian communities originally associated with the Apostle John.

Paul and the Romans

Scholars broadly agree that the Apostle Paul wrote the letter to the Romans, probably sometime between 52-58 CE. Paul was an educated and zealous Jewish person, a Pharisee, who persecuted the early church. His life changed when he dramatically encountered Christ on the road to Damascus, where he had intended to arrest Christians (people “of the Way” in the language of Acts) present in the synagogue. (See Acts 9; Acts 22:1-3.) Contemporary scholars debate whether to call this event a “conversion” or a “calling” or “commissioning” of Paul. Paul did not renounce Judaism, but understood the revelation of Christ as belonging to the Jews first, so Paul was not really converted “away” from Judaism (see Romans 1:16). Yet, Paul did consider himself an emissary, and Apostle, of God’s mission of reconciliation in Christ to the Gentiles — “to the Jew first, and also to the Greek” (Rom. 1:16).

In our study of 1 Corinthians, we discussed how Paul established the Christian community in Corinth in the course of his missionary journeys. In his letter to the Romans, Paul acknowledges that he did not originally convert the Romans — that is, that he did not found the congregation in Rome. He also says he does not plan to visit them at least until after his trip to Jerusalem and a subsequent trip to Spain (Rom. 15:20-29).

We do not know exactly how the church in Rome was founded or precisely how its beliefs and practices related to those of the congregations founded by Paul in Greece, John in Asia Minor, or Peter in Jerusalem. The concluding portion of the book of Acts, however, suggests Paul came to be well regarded by the Roman Christians. There are some details in the book of Acts that are hard to pin down compared to the available extra-Biblical archeological and documentary evidence. It may be that the Apostle Luke, who compiled Acts, confused or interwove some of the events and actors, or that we lack context for some of Luke’s narrative. But a comparison of Acts, 1 and 2 Corinthians, and Romans gives us a good sense of when the letter to the Romans was probably composed.

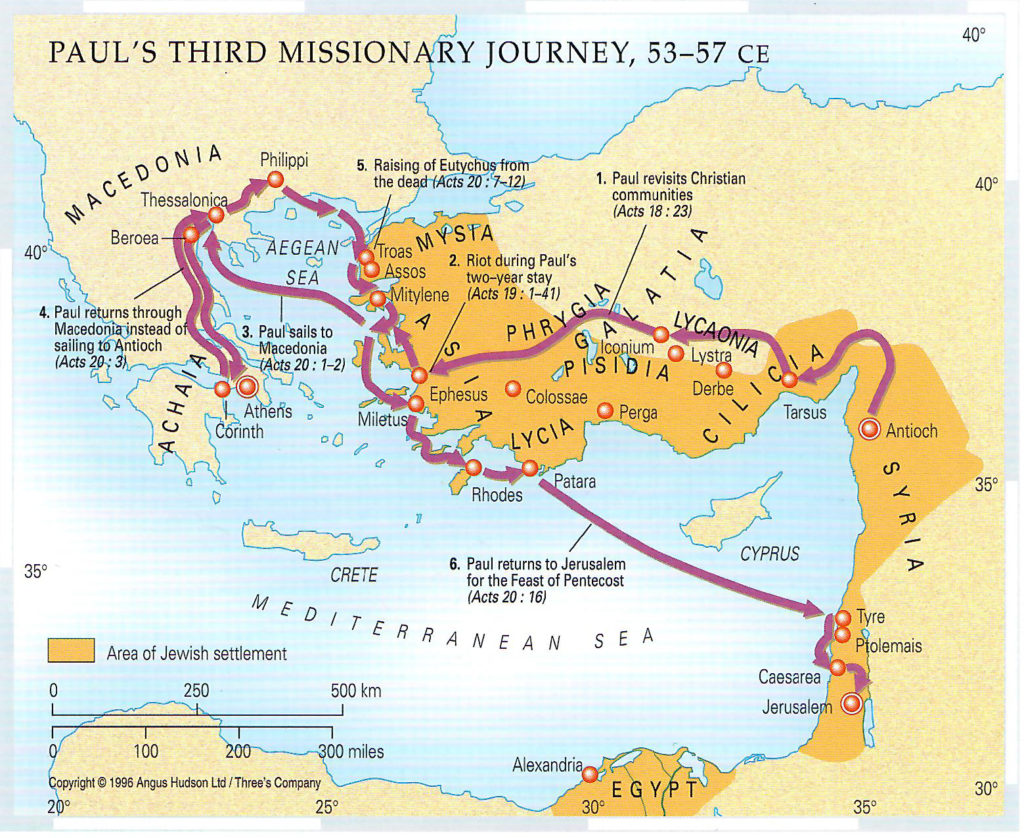

Acts 18 tells us that Paul stayed in Corinth “for a considerable time” and then began his third missionary journey, ending in Jerusalem. This map shows the course of Paul’s third journey as described in Acts 18-24:

In Jerusalem, Acts 24 tells us, Paul was violently opposed by the Jewish leaders and arrested by the Roman authorities. Remember that this is still the “Second Temple” period in Jewish history. The Temple in Jerusalem had been rebuilt by the Judean returnees under the Persian King Cyrus hundreds of years earlier, and was magnificently expanded by Herod the Great about two decades before the birth of Jesus. By the time of Herod and his heirs (the “Herodian Dynasty”), Jerusalem and the area that previously encompassed ancient Israel was under Roman control. Many Jews believed that Roman rule would be overthrown and that the promises in Isaiah and other parts of their scriptures of an ideal kingdom under an heir to King David would be fulfilled.

Given this context, we should pause here for a moment and ask why the Jews violently opposed Paul, even to the point of enlisting the Roman authorities to arrest him. Paul was a highly educated Jew. As we will see throughout our study of Romans, Paul as a follower of Jesus remained a faithful Jew, and his message to the Jews — the Gospel he preached to the Jews — was thoroughly Jewish. It is a mistake, one of the most awful mistakes in Christian history, to oppose the message of Christian faith to the heart of Jewish faith.

But, as we also see with Jesus in the Gospels, the claim that Jesus was the expected messiah, that Jesus rose from the dead, and indeed that Jesus was in some way divine, caused offense. Paul’s message caused intra-Jewish tensions when he preached in the Synagogues.

Further, Paul argued that Gentiles should be fully included in the community of God’s people, which led to practices strictly observant Jews considered compromised. (See, e.g., Acts 21;28-29.)

In addition, although the Romans gave the Jews more independence than they did for many other people in occupied territories, tensions were high. Pilate agreed to execute Jesus to prevent a riot and to quash the expectation that a Jewish warrior would arise to throw off Roman rule. The Jewish leaders in many cities were wary of zealots who might stir up popular unrest or attract unwanted attention from the Romans. Paul may have represented such a threat, as he often attracted plenty of attention. Acts 19:23-41, for example, tells us a riot nearly broke out in Ephesus when pagan craftsmen accused Paul and his comrades of hurting their business.

Finally, when we hear the word “Jews” today, we think of a religious, ethnic, or cultural group or groups present in various parts of the world, in contrast to other religious, cultural, or ethnic groups. The word Ioudaioi as used in the New Testament, however, connotes the native residents of the Roman province of Judea. It’s true that the New Testament usage includes the religious, cultural, and ethnic assumptions that the specific people involved are the heirs of ancient Israel, in contrast to the Romans, but the context of the usage is somewhat different than it would be today. The tensions between the Jewish leaders and Paul, then, should be seen as tensions between a dominant group and a new sub-group within the same religious, cultural, and ethnic matrix, not as a contest between “Christians vs. Jews.”

According to Acts 24, at the instigation of the Jewish leaders in Jerusalem, the Roman authorities brought Paul under guard to Caesarea, a city built by Herod the Great that became the provincial capital of Roman Judea, to appear before the Roman Governor, Felix. Paul was kept in a form of protective custody in Caesarea for two years. (Acts 24).

When a new Governor, Festus, took power, according to Acts 25, the Jewish leaders agitated for a hearing against Paul. At an initial hearing before Festus, Paul invoked his right as a Roman citizen to a hearing before the Emperor — that is, before the courts in Rome. (Acts 25:10). Meanwhile, King Agrippa and his sister, Bernice, arrived in Caesarea to welcome Festus, and Festus put the case before the King. King Agrippa was Herod Agrippa II, the Jewish client ruler who had been given the title “King of the Jews” by the Roman Emperor Claudius.

King Agrippa heard Paul’s defense and agreed that Paul had committed no crime under the law. However, he held that Paul’s initial appeal to Roman justice meant Paul must be transferred to Rome for trial. (Acts 26:30-32.) The account of Agrippa and Festus’ treatment of Paul in response to the agitation of the Jewish leaders perhaps offers a microcosm of the cultural, religious, and political tinderbox of the Judean territories at that time — no less than Pontius Pilate’s handling of Jesus in Jerusalem about 20 years prior reflected the same fraught dynamics. (About a decade after this event, Herod Agrippa II would be overthrown by his Jewish subjects in a revolt that would lead to the destruction of the Second Temple by the Roman Emperor Titus in 70 CE. During the revolt, Herod Agrippa II sided with Rome.)

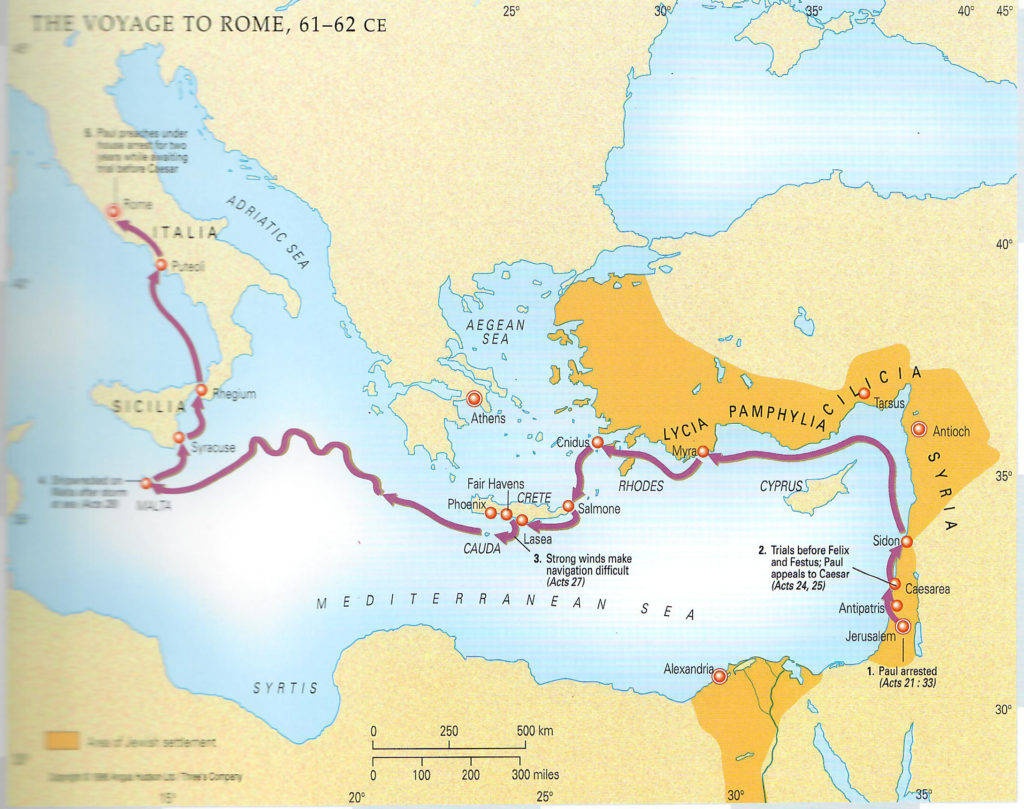

Paul’s trip to Rome, by sea, became an adventure involving a shipwreck and a stay on the island of Malta before putting in at the harbor town of Puteoli and traveling overland from there to Rome. (Acts 28.) Acts 28:14-15 says Paul and his party found fellow Jesus-followers (“brothers”) in Puteoli and that he was visited by other “brothers” “as far as the Forum of Appius and Three Taverns” to visit with Paul and his companions. The Forum of Appius and the Three Taverns were stations on the Appian Way, a road leading into Rome. Upon arriving in Rome, Paul “was allowed to live by himself, with the soldier who was guarding him.” (Acts 28:16.) The book of Acts concludes with the note that Paul lived in Rome for two years “at his own expense and welcomed all who came to him, proclaiming the kingdom of God and teaching about the Lord Jesus Christ with all boldness and without hindrance.” (Acts 28:30.) Early sources outside the Bible say Paul was martyred in Rome under the Emperor Nero sometime between 64-68 CE, but we have no contemporaneous accounts of Paul’s death.

It seems likely, then, that Paul’s letter to the Romans was written before he left Corinth, that is, before his third missionary journey. The letter to the Romans says Paul had not yet visited the Roman church and anticipates the continuation of his missionary journeys, suggesting he was not yet in Roman custody awaiting trial. There is some disagreement about the precise relationship between Romans and 1 and 2 Corinthians. There is also some disagreement about whether Romans 16 (the final chapter) was originally a separate letter. In any event, it is likely that the letter to the Romans was composed after 1 and 2 Corinthians, perhaps while Paul was visiting at Corinth to pick up the collection of donations for the poor in the church in Jerusalem. (See Romans 15:22-29.)

Purpose of the Letter

Like Paul’s other letters, this text is a letter, addressed to an early Christian community in a specific time and place. However, unlike his other letters, Paul does not have a direct pastoral relationship with the Roman church, and we cannot identify a specific dispute or cluster of disputes to which Paul is responding in Rome. The letter itself seems more broad, and in some ways more theologically dense, than Paul’s other letters.

Although the letter is in some ways broad, it does address a specific theological problem common to the early Christian congregations and, as we have seen central to Paul’s own experience: the relationship between Jewish and Gentile followers of Jesus. These tensions within the Roman church might have been shaped by a particular event under the Roman Emperor Claudius.

Claudius expelled the Jews from Rome in or around 49 CE. As we have noted, the Romans always maintained strained relationships with the Jewish communities under their domain. The Jews were allowed a degree of freedom even though their religion, unlike the religions of other conquered peoples, could not assimilate easily with Roman paganism. There were occasional armed clashes with Jewish zealots, tensions were sometimes high, and at times the Jews were expelled from the cities.

An intriguing comment by the Roman historian Suetonius states that “Since the Jews constantly made disturbances at the instigation of Chrestus, he [the Emperor Claudius] expelled them from Rome.” This might suggest that Claudius confused traditional Jews and the Jewish Christians, who were followers of “Chrestus.” Jesus is often referred to as Iesous Christos — Jesus Christ — in the New Testament (including in Romans 1:1). “Christos” is the Greek word for “anointed one,” used in the Greek version of the Old Testament for the Hebrew word mashiach (“messiah”), also meaning “anointed.” The Roman authorities under Claudius may have thought the title “Christos” was the name of a Jewish leader who was stirring up trouble. In this case, the Jewish Christians may have been expelled for proselytizing.

In Romans 16:3-4, Paul greets Prisca and Aquila as members of the Roman congregation. In Acts 18, Paul stays with Priscilla and Aquila, fellow tentmakers, who were expelled from Rome by Claudius. Based on this evidence, some scholars suggest Priscilla and Aquila, along with other Jewish Christians, had returned to Rome after things quieted down, and that Paul’s letter was written to address tensions between the returning Jewish Christians and the Gentile believers who had remained in Rome. This could be consistent with Paul’s work among the Corinthians, who were being influenced by Apollos as well as by Paul. Suetonius wrote his history about 70 years after the events, however, so we can’t be sure of this possible background to Paul’s letter.

It could be, then, that Paul writes for the broader purpose of establishing certain themes concerning his ministry among the Gentiles that he hopes to take up again, perhaps amidst some anticipated tension or opposition, in some future season. Perhaps the letter in some ways represents Paul’s effort to leave a record or place-marker in the fledgling church as it then existed in an important region — the Imperial Capital — while he is otherwise engaged in missionary activities elsewhere. As Luke Timothy Johnson suggests, the letter might have served as a kind of “recommendation letter” from Paul on his own behalf in support of his missionary journeys, which eventually were meant to include Rome.

Theological Themes

In some ways Romans is a tale of two letters. The first part of the letter is a dense, sustained theological argument, while the second part is more practical and pastoral. As we’ll see, however, the pastoral part of the letter is also theological, in that it puts missional “legs” on the themes in the letter’s first part.

Readers and commentators have always noticed that Paul focuses on sin, law, judgment, atonement, faith, election, God’s relationship with the Jews and Gentiles, and “justification.” These are, of course, the weighty themes of the whole Bible!

Historically, “Eastern ” (Orthodox) and “Western” (Catholic) readings of Romans have differed on whether, or in what way, Paul develops a doctrine of “original sin,” as well as on Paul’s picture of how Christ’s death atones for our sins. Catholic and Protestant readings of Romans, meanwhile, historically differed sharply concerning the meaning of “justification” and the relationship of this concept to election, faith, law, and works.

These differences still persist, particularly in more polemical writings by adherents to these different variants of Christian thought and practice. Since the early 1970’s, however, there has been a growing view among scholars of different confessional backgrounds that we must read Paul as a faithful late Second Temple period Jewish scholar and activist (or zealot), who had dramatically encountered what he believed to be the risen Messiah, in a time when Jewish thought was ripe with eschatological expectations against Roman oppression. This view is not uncontested. Some scholars continue to press the “Lutheran” reading that Paul sharply contrasted his message of grace against the Jewish Law. In my view this “new” perspective on Paul in the Second Temple Jewish context makes more sense of Paul’s letters, and the materials in Acts, than the “Lutheran” reading.

I put “Lutheran” in scare quotes above because the dialectic of law and grace that emerged within various streams of Protestant thought into the 19th and 20th Centuries was more nuanced than the “new perspective” writers often suggest. I think Paul sometimes writes in the “Lutheran” mode and sometimes in the “apocalyptic” mode highlighted by many new perspective scholars. I don’t think the “Lutheran” and “new perspective” readings of Paul always have to be mutually exclusive.

One important theme of the “new perspective” reading is that, when Paul writes about faith (pistis), he is not primarily writing about a voluntaristic decision by an individual. As we will see, he is focused most often on the faithfulness of Jesus Christ, which secures the collective salvation of Jew and Gentile alike. And, likewise, when Paul writes about election, he is not imagining God choosing individuals for salvation or damnation. Rather, he is wrestling with God’s faithfulness to his election of Israel in light of the new experience of God’s inclusion of the Gentiles.

Of course, Paul does seek to persuade individuals — each of us — to follow Jesus as part of the community of God’s people. But a richer understanding of this context can help us avoid distortions of Paul’s message.